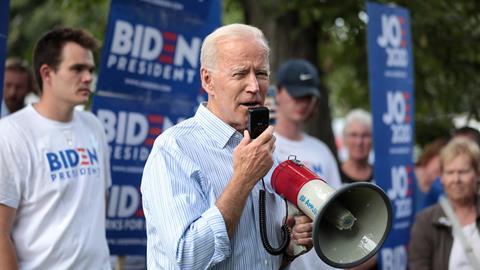

As the world reflects on Joe Biden’s victory, here are a few things to look out for in terms of the impact on the tackling of financial crime

1. Will the US finally bring in robust corporate transparency laws?

The United States is arguably trailing much of the developed world, including the EU and the UK, when it comes to corporate transparency. It has yet to bring in a federal register of beneficial owners, despite the Financial Action Task Force raising the issue on more than one occasion and describing this absence as a “significant shortcoming” in March.

Last year, Steven M. D’Antuono, Acting Deputy Assistant Director at the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) told the Senate that no US states currently require information about the identity of individuals who own or control legal entities upon their formation. He said that the “pervasive use of front companies, nominees or other means to conceal the true beneficial owners of assets is a significant loophole in this country’s AML regime”.

Although President Biden will not be able to direct the passage, or non-passage, of the bill through congress directly, presidential support does tend to have a big influence, particularly for a new incumbent.

The real question is will Biden use this influence? And if the bill is passed into law, would he ensure there is sufficient support and funding in place to ensure it can be enforced? The new President has to date been largely silent on the issue of corporate transparency, and financial crime full stop, but the hope is that a Democratic president would be more likely to ensure proper enforcement funding is in place than a continued Trump presidency would’ve done.

2. Would a Biden administration seek to reverse the fall in white collar crime prosecutions?

Many commentators have noticed a collapse in white collar criminal cases filed in federal courts under Trump’s administration. Figures from the Attorney General’s office show a 17% drop in white collar cases in the first two years of Trump’s presidency compared to the last four years under Obama. Non-prosecution agreements for Bank Secrecy Act offences, such as money laundering, bribery and fraud, also fell 57% over the same period with agreements involving financial institutions dropping 37%. By contrasts, criminal cases for violence and immigration offences rose 31% and 32%.

The US constitution’s separate of powers notwithstanding, it seems evident that the Trump administration oversaw a more lenient approach to financial crime than under Obama.

This is not to say however that the pendulum will necessarily swing back the other way once Biden is in the White House. Biden’s Criminal Justice Plan is silent on financial crime, focusing more on reforming the prison system, reducing the number of people being imprisoned and strengthening rehabilitation. Biden specifically wants to cut the number of people being imprisoned for drugs offences, could this in turn pave the way for more of a focus on upping numbers of prosecutions for white collar crime and money laundering?

3. Are we likely to see a pivot away from sanctions?

Trump had been notable for his ramping up of the use of sanctions as a key foreign policy tool, while pulling back on troops deployment and disengaging with international bodies. The Trump administration imposed sanctions on more than 900 entities or people each year over four years, an 80% increase compared to under Obama, according to figures compiled by the Wall Street Journal from Dow Jones Threat & Compliance. In 2020 alone, more than 700 entities or people have been added to the Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctions blacklist. In the past week Trump has introduced further sanctions on Cuba

However Biden has also talked tough on sanctions, tweeting criticism of Trump opposing sanctions over China’s human rights violations. He also mentioned in the 22 October debate that the only reason that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un refused to meet Obama was because of the latter’s strong sanctions policy, hinting he might be tempted to do the same thing again.

From an anti-money laundering point of view, increased sanctions activity leads to more work for compliance professionals at financial institutions. Jurisdictions have little choice but to comply if they want to trade in the dollar, so the banks in turn have to spend a large amount of resource ensuring they don’t fall foul of the rules.

4. Will Biden want to see reform of transaction reporting following the high-profile FinCEN Files leak?

The publication of the leaked FinCEN Files drew surprisingly little comment from either of the candidates last month (that is, if you discount Trump’s flagging of allegations involving Hunter Biden). The publication of suspicious activity reports showing banks moved $2trillion in payments they believed could be suspicious between 1999 and 2017. Although there was a flurry of anger on the airwaves towards the banks, the issue doesn’t seem to have translated into political positions among the candidates, which is perhaps understandable given the priority of other global issues currently. Some in the banking sector have argued that the SARs system is to blame, while others criticised the leaking of the files as unhelpful for intelligence-sharing. It is noticeable however that one of the strongest advocates for reform has been Linda Lacewell, superintendent of the New York State Department of Financial Services. Lacewell branded SARs as a “free pass” and called for sanctions on bankers who allow corrupt transactions.

Lacewell is an influential former Democratic adviser so it is just possible that Biden would be more likely to listen, particularly if her views represent a wider train of Democratic thought

The safe betting would be on no major changes to the SARs system in the short term, however.

No comments yet