Recently, well-publicised research by data scientists at Imperial College in London and Université Catholique de Louvain in Belgium as well as a ruling by Judge Michal Agmon-Gonen of the Tel Aviv District Court have highlighted the shortcomings of outdated data protection techniques like “Anonymisation” in today’s big data world.

Anonymisation reflects an outdated approach to data protection developed when the processing of data was limited to isolated (siloed) applications prior to the popularity of “big data” processing that involves widespread sharing and combining of data. This is why the Israeli judge in the above-cited case highlights the relevance of state of the art data protection principles embodied in the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in her ruling that:

Increasing the technological capabilities that enable storing large amounts of data, known as “big data”, and trading this information, enables the cross-referencing of information from different databases, and thus also trivial information such as location, may be cross-referenced with other data and reveal many details about a person, which infringe upon his privacy.

Given the scope of data collection and use of information, the matters of anonymisation and re-identification have recently become important and relevant to almost every entity in Israel – both private and public – which holds a substantial amount of information.

Information technologies bring new challenges and ongoing privacy vulnerabilities. One of the solutions that has been discussed in recent years is that of privacy engineering (Privacy by design), i.e., the design of technological systems in advance, to include protection of privacy.

A binding rule regarding privacy engineering was established in the European Union. Regulation for the Protection of Personal Data Article 25 of the GDPR General Data Protection Regulation (which came into effect in 2018) imposes a duty on the data controller to implement appropriate and effective technological and organisational measures both at the stage of system planning and in the stage of information processing, in other words, requiring a process of privacy engineering.

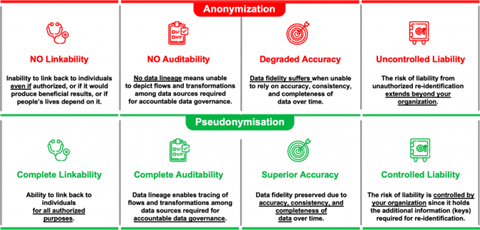

Anonymisation involves uncontrolled liability / pseudonymisation involves controlled liability

For data to be “anonymous,” the data must not be capable of being cross-referenced with other data to reveal identity. This very high standard is required because if data DOES satisfy the requirements for “Anonymity,” it is treated as being outside the scope of legal protection under the GDPR. Why? Because of the very “safe” and protected nature of the data that actually satisfies the requirement of not being cross-referenceable or re-identifiable. The Israeli court in Disabled Veterans Association v. Ministry of Defense highlighted that this is generally NOT the case in today’s world of big data processing.

Today, data that is held by a processor is often readily linkable with data that is beyond the control of the processor thereby enabling re-identification and exposing the processor to liability for failure to protect privacy. When data held by third parties beyond the control of a processor can be used to cross-reference and re-identify individuals, the processor is exposed to potential liability not under its control – i.e., uncontrolled liability.

Pseudonymised data (as defined under GDPR Article 4(5)), unlike irreversibly anonymised data which by definition cannot be linked back to a data subject, remains within the scope of the GDPR as personal data. According to GDPR definitional requirements, data is NOT pseudonymised if it can be attributed to a specific data subject without requiring the use of separately kept “additional information” to prevent unauthorised re-identification.

Pseudonymised data embodies the state of the art in Privacy by Design engineering to enforce dynamic (versus static) protection of both direct and indirect identifiers (not just direct). The shortcomings of static approaches to data protection (e.g., failed attempts at anonymisation) are highlighted in two well-known historical examples of unauthorised re-identification of individuals using AOL and Netflix data.

These examples of unauthorised re-identification were possible because data was statically protected without the use of separately kept “additional information” as now required for compliant pseudonymisation under the GDPR.

GDPR Privacy by Design principles as embodied in Pseudonymisation require dynamic protection of both direct and indirect identifiers so that personal data is not cross-referenceable (or re-identifiable) without access to “additional information” that is kept securely by the controller. Because access to this “additional information” under the control of the processor is required for re-identification, exposure to liability is under the control of the processor – i.e., controlled liability.

Background and benefits of GDPR-compliant pseudonymisation

GDPR Article 25(1) identifies pseudonymisation as an “appropriate technical and organisational measure” and Article 25(2) requires controllers to “implement appropriate technical and organisational measures for ensuring that, by default, only personal data which are necessary for each specific purpose of the processing are processed.

That obligation applies to the amount of personal data collected, the extent of their processing, the period of their storage and their accessibility. In particular, such measures shall ensure that by default personal data are not made accessible without the individual’s intervention to an indefinite number of natural persons.”

The importance of dynamically protecting both direct and indirect identifiers is highlighted in Article 29 Working Party Opinion 05/2014, written in anticipation of the GDPR, which states:

It is still possible to single out individuals’ records if the individual is still identified by a unique attribute which is the result of the pseudonymisation function [i.e., a static attribute that does not change, in contrast to a dynamic attribute which does change]…

Linkability will still be trivial between records using the same pseudonymised attribute to refer to the same individual….

Inference attacks on the real identity of a data subject are possible within the dataset or across different databases that use the same pseudonymised attribute for an individual, or if pseudonyms are self-explanatory and do not mask the original identity of the data subject properly…

Simply altering the ID does not prevent someone from identifying a data subject if quasi-identifiers remain in the dataset, or if the values of other attributes are still capable of identifying an individual.

State of the art pseudonymisation not only enables greater privacy-respectful use of data in today’s “big data” world of data sharing and combining, but it also enables data controllers and processors to reap explicit benefits under the GDPR for correctly pseudonymised data.

The benefits of properly pseudonymised data are highlighted in multiple GDPR Articles, including:

- Article 6(4) as a safeguard to help ensure the compatibility of new data processing.

- Article 25 as a technical and organisational measure to help enforce data minimisation principles and compliance with data protection by design and by default obligations.

- Articles 32, 33 and 34 as a security measure helping to make data breaches “unlikely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons” thereby reducing liability and notification obligations for data breaches.

- Article 89(1) as a safeguard in connection with processing for archiving purposes in the public interest; scientific or historical research purposes; or statistical purposes; moreover, the benefits of pseudonymisation under this Article 89(1) also provide greater flexibility under:

- Article 5(1)(b) with regard to purpose limitation;

- Article 5(1)(e) with regard to storage limitation; and

- Article 9(2)(j) with regard to overcoming the general prohibition on processing Article 9(1) special categories of personal data.

- In addition, properly Pseudonymised data is recognised in Article 29 Working Party Opinion 06/2014 as playing “a role with regard to the evaluation of the potential impact of the processing on the data subject…tipping the balance in favour of the controller” to help support Legitimate Interest processing as a legal basis under Article GDPR 6(1)(f). Benefits from processing personal data using Legitimate Interest as a legal basis under the GDPR include, without limitation:

- Under Article 17(1)(c), if a data controller shows they “have overriding legitimate grounds for processing” supported by technical and organisational measures to satisfy the balancing of interest test, they have greater flexibility in complying with Right to be Forgotten requests.

- Under Article 18(1)(d), a data controller has flexibility in complying with claims to restrict the processing of personal data if they can show they have technical and organisational measures in place so that the rights of the data controller properly override those of the data subject because the rights of the data subjects are protected.

- Under Article 20(1), data controllers using Legitimate Interest processing are not subject to the right of portability, which applies only to consent-based processing.

- Under Article 21(1), a data controller using Legitimate Interest processing may be able to show they have adequate technical and organisational measures in place so that the rights of the data controller properly override those of the data subject because the rights of the data subjects are protected; however, data subjects always have the right under Article 21(3) to not receive direct marketing outreach as a result of such processing.

If you found this article helpful, you may enjoy the discussion on “Functional Separation” in Benefits of Pseudonymisation vs. Anonymisation Under the GDPR.

By Gary LaFever, CEO at Anon

No comments yet