Tory MP and candidate for future British Prime Minister Kemi Badenoch has likened net zero to “unilateral economic disarmament.” Is this right?

ESG wasn’t mentioned by name — but the inference was clear; in her speech announcing her decision to run for leader of the UK Conservative Party, Kemi Badenoch focused on many of the issues associated with ESG.

She complained about “too many well-meaning regulations slowing growth and clogging up the arteries of the economy.”

She said: “Our ability to defend the free market as a way to help people prosper has been undermined. It has been undermined by a willingness to embrace protectionism; it has been undermined by retreating in the face of Ben and Jerry’s tendency — those who say a business’s main priority is social justice, not productivity and profit.”

And she referred to net zero targets, which she said were “set up with no thought to the industries in the poorest areas of the country. The consequence is to displace emissions to other countries: unilateral economic disarmament.”

Today, I am focusing on her comments regarding net zero — the “Ben and Jerry tendency” is a topic for another day.

Net zero the problem that isn’t a problem

So what about net zero? It is a popular trope.

Inflation is soaring; the oil and gas price has hit the stratosphere. Households are struggling to pay for the basics. A recession may hit the UK, Eurozone and perhaps the US economy later this year.

So here is the message that net zero critics like Ms Badenoch seem to be sending: Get real. This is not the time for niceties and luxuries like renewables; we need oil, and we need it now.

James Murray, Editor of Business Green, took to Twitter to put the case for defence. He Tweeted: “The idea net zero was adopted with ‘no thought’ for the impact on industries and regions is demonstrably untrue. There are literally thousands of pages of government and independent analysis on this very question.

“It is why governments protected certain industries from carbon prices, handed them tax breaks, and are working to locate emerging low carbon industries in industrial hubs.”

The Badenoch critique is odd. Renewables represent a massive economic opportunity for many of the poorest areas of the UK.

Take, for example, Net Zero Teesside — a carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) project. Back in 2020, Tees Valley Mayor, and member of the Conservative Party, Ben Houchen, said: “When Iron Ore was discovered in the Cleveland hills in 1850, it sparked a revolution that transformed our region and gave birth to the Infant Hercules that built the world and changed the lives of everyone in Teesside like never before. Today we are on the cusp of another revolution just as seismic and has the potential to be as transformational for the people of Teesside, Darlington and Hartlepool.”

He added: “Investing in the clean industries of the future is not just important in achieving net-zero, it’s also crucial for jobs.”

So that’s the first problem with Kemi Badenoch’s net zero statement— it is an exceptional economic opportunity, not a threat.

Cost of energy

Right now, people are fretting about their energy bills. Inflation is back — although the jury is out on whether it is back temporarily or permanently.

What people want is cheaper energy — and there is very little in the way of short-term fixes available. It takes time to ramp up energy production, whether the source is oil, gas, coal, nuclear or renewables. But it turns out that investing in renewables is one of the quickest routes to increasing energy supply.

According to an article in the Guardian published in 2014, it takes ten years to scale up a shale gas site from scratch. The Climate Change Committee (in the UK) claims that once a North Sea oil project is granted a licence, it can take 28 years before oil and gas start to flow.

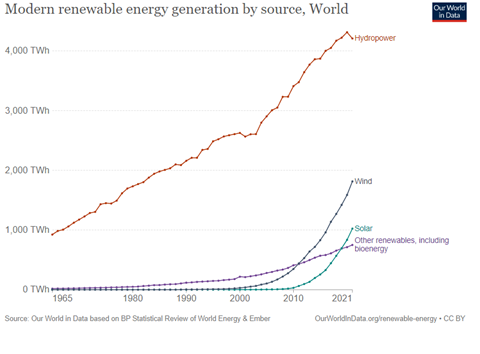

Compare the above with creating a wind or solar farm. Solar’s share of global capacity increased five-fold from 2010 to 2020.

By the first quarter of 2020, renewable’s share of global electricity generation was 28 per cent. Global energy production from wind increased four-fold between 2010 and 2020.

The above stats provide all the evidence you need.The rise of renewables has been a phenomenal success story — a story of falling costs, job creation and incredibly rapid scaling. Do renewables represent the fastest route to cost-effective energy security? All the evidence screams yes.

The trope that won’t go away

Renewable (and by default, net zero) critics are determined to find the fatal flaw. So while the renewables critique slowly disappears like coal from a coal mine, they desperately try and find new rationales.

The two most popular critics of the moment are the blatantly disproven claim that the carbon footprint is making renewables prohibitive. And the Badenoch critique.

Concerning the first argument, as a July 2022 report from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) states: “The lifetime cost per kWh of new solar and wind capacity added in Europe in 2021 will average at least four to six times less than the marginal generating costs of fossil fuels in 2022.” And that’s lifetime cost, i.e. including the cost of construction.

Furthermore, as this 2021 report from French utility company ENGIE states: “Wind turbine components are essentially 100 per cent recyclable.”

→ SEE ALSO: ”These bike shelters are made from wind turbines.”

But Kemi Badenoch focuses on another argument, the assertion that net zero merely has the effect of exporting carbon footprints to other countries — net zero is unilateral economic disarmament.

Returning to James Murray, he Tweeted: “It is also untrue that UK action has fully displaced emissions to other countries. ‘Carbon leakage’ can be an issue (hence policies to tackle it), but overall global emissions are starting to flat line as GDP growth and emissions decouple.

“And finally, it is completely false the UK has embarked on ’unilateral economic disarmament. Ninety per cent of global GDP is covered by net zero goals; the Paris Agreement is signed by every country on Earth.

The Chinese elephant in the living room

Renewable critics love to cite China. “Whatever we do is an irrelevance because of the volume of CO2 burned in China,” they say.

It is not a credible argument, and it is not credible for several reasons. I will leave the most important reason to last:

- China is the world’s factory — when it burns CO2 to a large extent, it does this by making goods the West consumes.

- China’s CO2 emissions are not excessive on a per capita basis.

- The biggest problem with CO2 is one of legacy — historical CO2 emissions in the West; China’s contribution to cumulative CO2 emissions remains small relative to the West.

- But the killer argument, of course, is the extraordinary level of investment in China into renewables. China is projected to account for 45 per cent of global renewable capacity additions in 2022-2023.

The China syndrome

In fact, China’s expansion into renewables is so massive that many experts fear it is becoming too powerful and poses a security threat to the West.

So which one is it? Is China the bad boy of CO2 emissions or too dominant in renewables? It can’t be both.

Cognitive dissonance

There is extraordinary cognitive dissonance in the renewables debate. The renewables revolution is perhaps the best technology/economic news of my lifetime, so why try to dismiss or belittle this remarkable opportunity?

Is the problem that free market fundamentalists can’t get their heads around the way fears over climate change have created an opportunity that the markets might otherwise have missed?

Is the problem that too many people are wedded to the past and are afraid of change — conservative with a small c, Luddites in the corridors of power?

Or is the problem the fossil fuel lobby and the trillions of dollars worth of proven oil reserves?

Renewable energy is a disruptive technology — and as Kodak, Nokia and Blockbusters could confirm, disruptive technology is terrifying for incumbents.

But those who react to it by manufacturing reasons not to want it are on the wrong side of history — Chapter 11 welcomed many companies that denied disruptive technology, and reaction against net zero would create a sad and disastrous chapter for the UK economy.

No comments yet